TextureForge: The Sunk Cost of the Python Prototype

Complexity is a relentless auditor, and my current prototype just failed its performance review.

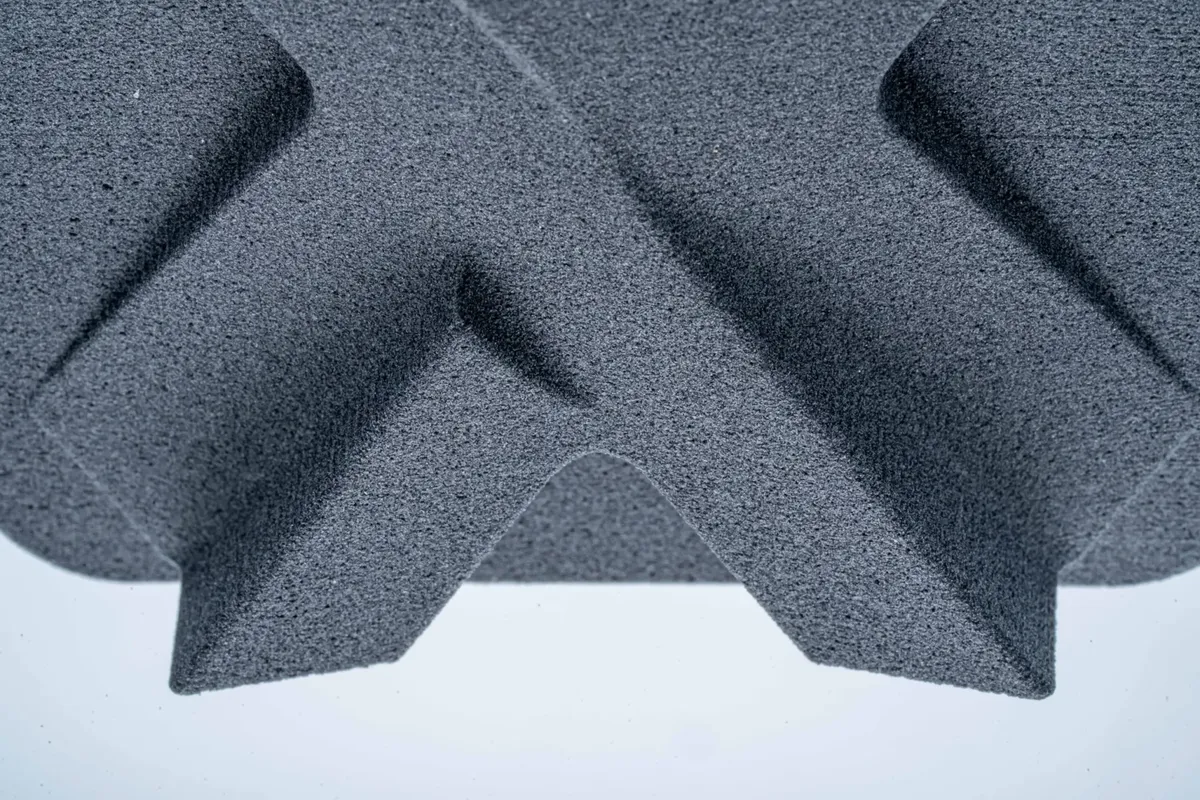

I have a naming problem. My last project was SinterForge—an attempt to replicate the tactical, high-quality feel of SLS (Selective Laser Sintering) prints using a Mars 5 Ultra resin printer. There was no actual metal involved; it was about the “grip.” I wanted that rugged, sturdy, nylon-like finish on parts that otherwise felt like clinical, liquid plastic.

It turns out that chasing the “perfect feel” is an expensive way to learn about the limits of modern geometry engines.

The Blender Dead End

Before I wrote a single line of Python, I tried to do this the “easy” way: Blender Geometry Nodes. It seemed like the logical choice. Blender has a massive, C-based engine and a visual scripting language.

But even with the simplest input geometry, I hit a ceiling. Applying a high-frequency displacement to simulate a 0.05mm grit meant Blender had to manage a mesh so dense the viewport became a slideshow. The moment I tried to Boolean a textured part into a functional assembly, the kernel just gave up. I realized then that if I wanted this tool to be usable, I’d have to build a dedicated engine for it.

Enter TextureForge. The name alone should have told me I was heading for a repeat performance of the “Forge” naming curse.

The Goal: Killing the “Liquid Plastic” Feel

The beauty of UV Resin printing is the resolution. Unlike FDM, you aren’t fighting layer lines; you’re fighting a soul-less smoothness. A fresh resin print has a “cheap toy” vibe that betrays the precision of the hardware. I wanted that gritty, rugged SLS-nylon finish. I wanted the parts to feel like they were industrial components, not cured by a screen in my guest room.

I built the TextureForge prototype in Python. It was a pragmatic start: PySide6 for the UI, Manifold3D for the heavy lifting, and Trimesh for geometry I/O. I had a working app in a weekend.

Then I tried to actually use it.

The Vertex Explosion

Here is where the “Director of Infrastructure” in me should have seen the bottleneck. My Mars 5 Ultra can resolve details down to the micron level. To give the printer enough “meat” to actually render a sintered texture, you have to subdivide the geometry until the facets disappear.

A standard, 20k-triangle STL is a lightweight toy. But to represent that high-frequency grit for a resin slice, you have to subdivide that mesh until it looks like fine sand. Suddenly, a simple 5MB file exploded into 10 million triangles.

Python/NumPy is fast for arrays, but when you are asking the CPU to generate OpenSimplex noise and displace 10 million vertices in a single thread, the “pragmatic” choice is a disaster. My RAM usage spiked to 12GB, the UI locked up, and I found myself staring at a spinning beachball while my workstation fans staged a protest.

The macOS OpenGL Curse

To add insult to injury, macOS decided to pick a fight with my 3D viewport. Apparently, PySide6 and PyVista (VTK) sharing an OpenGL context on Apple Silicon is like putting two cats in a bag.

I had to implement a “Detached Mode”—launching the 3D preview in a separate subprocess just to keep the window from flickering out of existence. It works, but it’s a “hack” that smells of technical debt. It breaks the “tweak and see” workflow that makes a tool like this actually fun to use.

Why We Move On (Again)

SinterForge (the project) failed because the simulation was too complex for the stack. TextureForge (the prototype) is “failing” because the software architecture is too slow for the fidelity that high-end resin demands.

As a builder, the hardest thing to do is admit your prototype is a dead end. But looking at the logs, the path forward is clear. If I want near real-time feedback on a 10-million vertex mesh, I have to leave the comfort of the CPU:

- The GPU Compute Route: Moving the noise generation to Compute Shaders using Rust + WGPU. Let the silicon designed for triangles do the triangle work.

- The Voxel Route: Using Signed Distance Fields (SDFs) and OpenVDB would make organic textures trivial without the self-intersection nightmares of explicit meshes.

Final Thought: Forge 3.0?

TextureForge isn’t a total loss. The algorithms work. The “Sintered” finish looks beautiful on the resin parts that actually manage to export—they feel sturdy, grippy, and “real.” But it’s a reminder that “Boring Tech” like Python is great for the UI, but when you’re fighting the physics of high-resolution geometry, you eventually have to get closer to the metal.

Maybe the next one will be called RustForge. At least the name would be honest about the language.

Technical Stack (The Prototype)

- GUI: PySide6 (Qt6)

- Math: NumPy & OpenSimplex

- Mesh Ops: Manifold3D (for watertight booleans)

- Viz: PyVista / VTK (with the mandatory macOS ‘detached’ hack)